|

|

|

|

| ||

|

biographische Artikel | biographic articles

| |

|

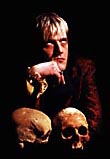

Reflections on Arriving Too Late to Experience Queer West Berlin Film Culture (...) [The super-8 filmmakers] were never really interested in making »good« films, but in making quick, inexpensive, personal, or socially and politically topical ones. The super-8 scene was distinguished by its collective spirit, its inventiveness both in filming and in exhibition, and its commitment to incorporating filmmaking into everyday life. In an important article on German experimental film history, Christine N. Brinckmann contrasts the »vitality« of the ‘80s super-8 scene with »the precision and formal mastery« of such earlier experimentalists, like Heinz Emigholz, W+B Hein, and Klaus Wyborny. »Unencumbered by the financial burdens and complex technology of 16mm production, they could work freely and spontaneously and develop a specific aesthetic. Many of their films bear the character of rough drafts and are short, intelligent, unpretentious, imaginative, and subversive.« For Michael Brynntrup, one of the significant figures in this scene and one of the most important queer filmmakers of his generation, »super-8 is not a format, but an outlook on life.« [1] Brynntrup maintains that »perfection doesn’t count as the most significant attribute of quality of a super-8 film.« Rather, the medium’s advantage resides in »its openness to newcomers. The unselfconsciousness of expressing oneself in this cheap medium is evident in many S-8 films. The simplicity of some S-8 films definitely stimulates many who still harbor fantasies. Some say to themselves »I can do that too,« and already make plans for their own S-8 film.« [2] Among the ‘80s West Berlin super-8 filmmakers, Brynntrup has remained one of the most productive and as a result has received well-deserved international attention.[3] He is also well known as one of many significant artist-filmmakers of his generation who has studied with Gerhard Büttenbender and Birgit Hein at the Braunschweig School of Art.[4] Though he only began his studies in Braunschweig in 1987, Brynntrup’s vast oeuvre has tended to be viewed retrospectively through this art school lens. Prior to 1987, however, he was arguably less concerned with the art world than with the world of small format filmmaking, collective film production, and squatter cinemas. Brynntrup arrived in West Berlin in 1982 after having spent half a year traveling in Italy, during which time he taught himself how to make films and found inspiration in part by reading his future teacher Birgit Hein’s seminal 1971 book on international avant-garde film, Film im Underground.[5] He quickly found his way into the burgeoning and welcoming super-8 scene and began writing regularly about developments within the movement for the taz. In his first article, he prepared readers for the first installment of the upcoming international Interfilm festival of super-8 films, organized by Gib-8 Kino, Gegenlicht film distribution and the film-performance project, u.v.a., and noted, with humility, »I myself am new in Berlin and am working on my first S-8 film. For me, this is going to be an exciting trip through the »New World« of super-8. I hope that something of this comes across to you.«[6] At the start of 1983, Brynntrup joined forces with almost twenty filmmakers, artists, musicians, and others active in the squatter cinema movement to form the collective OYKO (pronounced otsch-ko, like the Russian name for »eye« or »little eye«). OYKO, based in Kreuzberg/Neukölln, was one of many collectives active in the world of West Berlin super-8 filmmaking, distribution, and exhibition.[7] On July 17, 1983 in the Hasenheide park in Kreuzberg, OYKO put on their first public event: a five screen – better, a five bed sheet – open air projection of super-8 films accompanied by live music. Such an expanded cinema event was not untypical in the super-8 world, in which innovative and performative modes of film exhibition flourished. In its first year, OYKO went on to present films in the backyard of the squatter cinema, Eiszeit, and to produce the episodic film, Heimat? … Eine subjektive Ortsbestimmung (Homeland? … A Subjective Location) (FRG 1983), which screened in the 1984 International Forum of New Cinema.[8] For Heimat, Brynntrup contributed the film Der Rhein – ein deutsches Märchen (The Rhine – A German Fairy Tale) (FRG 1983), a reflection on the death of an uncle in combat in World War II at the age of 18. Incorporating family photos and home movies, as well as original material, this early film is a straightforward personal meditation on the banal persistence of daily life – both during and after the war – for a family in a small village in the Rhineland. Brynntrup maintains a subtle, yet sardonic critical perspective towards the family’s seemingly unreflecting relationship to National Socialism. This comes through most clearly in the beautiful and haunting superimpositions of war footage over the post-war home movies of Brynntrup’s family on vacation. As Maximilian Le Cain rightfully notes, Der Rhein can be seen as setting the tone for many of the Brynntrup films that follow, one of »playfulness shadowed by death.«[9] Skulls and skeletons do indeed abound in Brynntrup’s films. From 1988-1993, for instance, he worked on a visually stunning series of eight short films linked together as Totentänze (Death Dances) and unified through the recurrent appearance of a skull. In these films, the skull takes on different functions – as a drinking cup for a naïve young girl (Totentanz 1, FRG 1988) and as a mortar in which a handsome Aryan blonde boy crushes spices (Totentanz 2, FRG 1988) for example – and thereby reveals itself as a flexible, if provocative, symbol or »non-symbol,« as Brynntrup claims.[10] Though never entirely losing their connection to death, skulls adorn Brynntrup’s films like so many props in an artist’s studio or fashion accoutrements on the lapels of young rebels. Brynntrup’s aesthetic reappropriation of this loaded symbol suggests that for him death may as well be shadowed by playfulness. Brynntrup’s ‘80s abstract, personal films are not gay in the same way as, say, Praunheim or Speck’s films are – that is, in their explicit focus on »out« gay characters and on recognizable settings in the gay subculture. The homoerotic imagery and aesthetic sensibility that pervade his films nevertheless resonate with other queer work engaged in the erotic reorganization of the visual field. Brynntrup himself notes that his work often contains »certain gay moments.«[11] For example, his Stummfilm für Gehörlose (Silent Movie for Deaf People) (FRG 1984), a reflection on sign language and moving images, includes signs representing homosexuality, the penis and testicles, and his Tabufilm I-V (FRG 1988) deals quite explicitly with his own homosexuality and coming-out. Furthermore, almost every Brynntrup film confronts the viewer with the slightly affected – dare I say faggy – presence of the filmmaker himself, often in various forms of drag, as a kind of joker or fairy narrator figure. In an interview in 1989, Brynntrup noted, »I do believe it is clear that my films have been done by a gay filmmaker. I just haven’t done an exclusively gay film. And what is a homosexual film anyway? A traditionally narrated one with nothing more than a gay story. I do think gay identity exists, and so does gay culture, gay aesthetics.«[12] Like fellow super-8 filmmaker Derek Jarman, an important figure for Berliners working in super-8, Brynntrup’s films became more self-consciously gay or queer towards the end of ‘80s, as the AIDS epidemic led to an increased politicization of gay cultural production. In this sense, Brynntrup’s Totentänze resonate with other lyrical aesthetic responses to the epidemic. (...)

Marc Siegel, "Reflections on Arriving Too Late to Experience Queer West Berlin Film Culture" (excerpt on Michael Brynntrup), In: "Wer sagt denn, dass Beton nicht brennt, hast Du’s probiert? Film in West-Berlin der 80er Jahre / Who says concrete doesn’t burn, have you tried? West Berlin Film in the ‘80s", Hgs./Eds. Stefanie Schulte Strathaus & Florian Wüst (Berlin: b_books verlag 2008), 62-81.

[1] Michael Brintrup, »Alle Macht der Super Acht?«, in: Super-Acht in Berlin und anderswo, Berlin 1987, 41. Brynntrup (then spelling his name Brintrup) self-published this small brochure collecting articles he had written in 1982 and 1983 for a series on super-8 in the Berlin section of the daily newspaper die tageszeitung (taz), along with an additional article published in 1985 in the Berlin bi-weekly magazine tip. This brochure provides an indispensable insider look at the super-8 scene. Linkliste 'Interviews' | link list 'interviews' bio/monografische Einzel-Interviews | Linkliste 'Biografisches' | link list 'biographics' biografische Interviews und Artikel | Linkliste 'Monografisches' | link list 'monographics' monografische Interviews und Artikel | PRESSE-CLIPS | PRESS CLIPS kurze Auszüge aus der Presse | short excerpts from the press BIBLIOGRAPHIE | BIBLIOGRAPHY Einzel-Interviews und -Pressestimmen | | ||